The rapid growth of railway traffic created parallel growth in passenger movements and carriage of goods, thereby increasing the need for horses. Apart from conveyance of people and goods, the Victorian working horse was required for municipal services (fire engines, waste carts, postal services), machine power (shunting, hoisting, exceptional loads), and national defence (cavalry, artillery, transport). As an example of machine power duties, in 1864 it was claimed that about 90 horses were exclusively dedicated to shunting and sorting at Camden Goods Depot.

Land was primarily in the hands of large landowners and money for breeding was therefore available. A stallion at stud could serve up to 100 mares. Colts were broken in as geldings for later urban duties as they reached the optimum age of about five, with one in 50 perhaps retained as a stallion for stud purposes. Mares were kept for farm work and breeding, although they too could find themselves in urban employment and were favoured by many omnibus operators.

The typical life cycle of a male urban working horse was:

- Year 1 Weaned by farmer and sold to professional buyer

- Year 2 Castrated, broken in, sold on

- Years 3-4 Work on farms near urban/industrial centres

- Year 5 Sold for urban duties

- Years 6-9 First urban duty when at peak of powers

- Year 10-? Sold on for other urban or farm duties as strength and reliability declines.

Victorian London remained dependent on horses for the movement of goods and people despite the steam engine taking over ever more functions. Horses were so fundamental a power source that their service life became a business decision. Robert Bakewell, the best-known breeder of the eighteenth century, had sought to discover the animal that was the best machine for turning food into money, fodder being the major operations cost. The fodder market represented 10% of agricultural output by the end of the 19th century, with London by far the largest market.

The Victorians were generally unsentimental about horses. The mid-century Victorian attitude was expressed as ‘sentiment pays no dividend’: the horse had to earn its place as a source of power in competition with both man and machine. At the beginning of the century, the cost of keeping a horse was two to three times the hire of a day labourer, while the daily work of a horse was equal to that of five or six men. The cost of horse power was therefore about half that of manpower. It was reduced further over the next century, while the cost of manpower increased modestly.

The horse’s advantage over the machine started with low cost and flexibility, but as machines became more powerful, the horse had to work harder to compete. Competition with machines led to an increase in the size of horses, an increase in the horse’s workload, and a reduced working life. This trend was manifested by a US tram company that depreciated its horses at 7 per cent in 1880 and 16 per cent in 1885, an accountancy measure that appeared to reduce a fifteen-year working life to six years, although the horse must have had some second-hand value.

The weight of streetcar (tram) horses in the USA increased by 50 per cent between 1860 and 1880, allowing fewer horses per car. New York ‘street railway’ companies experimented with light steam-powered vehicles, but by 1870 these had been given up as too costly, the animal triumphing over the machine – with some help from regulation.

The quality of horses varied greatly. Brewery companies with their heavy cart horses had the highest standards, followed by parish vestries, railway companies and major carriers such as Pickfords. Omnibus, tram and cab horses were lighter and worked harder. The treatment of horses gradually became a greater issue through the 19th century. A number of breeding societies were formed in the 1870s and the London Cart Horse Parade was started at this time to encourage and reward better care of horses. Sir Walter Gilbey was a central figure in this movement, which also influenced the stabling of horses in terms of improved lighting, ventilation and drainage.

Growth in rail passenger traffic was constrained by competition with omnibus and tram services. Passenger journeys by rail in London increased from about 174 million in 1875 to 400 million in 1896. However, the share of rail in passenger traffic fell from 60 per cent to 40 per cent over the same period (Simmons 1986), as its dominance was undermined by the development of cheaper modes of transport: first omnibus services and then, from 1870, trams, both horse-drawn. The image shows North Metropolitan trams at Camden Road station (CLSAC).

The reductions in fares fostered the growth of suburbs and allowed workers to commute from more affordable parts of London. The competition not only captured much of rail’s market share but so reduced fares that certain rail services became unprofitable, notably workers’ trains.

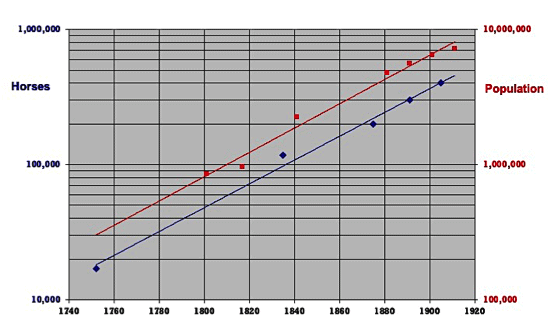

As implied by the logarithmic scale graph of population and horses in London over 1750 to 1910, the horse appears to have more than held its own against man and machine until the First World War.

To quote Jack Simmons: ‘In late Victorian London the horse took his revenge on the locomotive.’