London and Birmingham Railway

Robert Stephenson, son of George Stephenson, was appointed engineer-in-chief for the whole line in September 1833. He was not yet thirty. What had been his education and experience?

He spent the next ten years working for the L&BR, living first in Downshire Hill in Hampstead, and then from 1834 to 1843 at 5 Devonshire Place, one of a pair of semi-detached villas on the west side of Haverstock Hill, close to the corner with Belsize Grove. The house had a stable attached (out of view to left of photograph of 1903) where a groom, a carriage, a phaeton for his wife and one or two horses were accommodated. The photo (CLSAC) shows part of the turning circle in front of the house. The site is now part of the modern block of flats called Romney Court

His wife Fanny, whom he married in 1829, died childless in 1842 and is buried in the cemetery of St John’s, Hampstead, the church where they worshipped. Robert was the most senior engineer of the mid-19th century, whose public persona led to his interment in Westminster Abbey beside Thomas Telford, another highly distinguished civil engineer.

He was not only the Chief Engineer for the L&BR, establishing the construction technology for the railway age: he also took personal responsibility for the Primrose Hill contract, the first nine miles from Camden Town. This most difficult section of line, including Primrose Hill Tunnel and cutting, had driven the appointed contractor into bankruptcy after problems with ground conditions, particularly the swelling of blue London Clay exposed to the atmosphere. Stephenson must have walked this section of line innumerable times while supervising the direct labour he employed to replace the contractor’s workforce.

The engineering team was initially based in Kilburn. In May 1834 the office staff moved to the vacant Eyre Arms Tavern, seen here (Westminster City Archive) and named after a major landowner in the area.

The tavern was at 1 Finchley Road at the junction with Grove End Road. Its grounds were the scene of early balloon attempts, the last in 1839. It was demolished in 1928. Now the site of a block of flats, a plaque on the wall recalls its past.

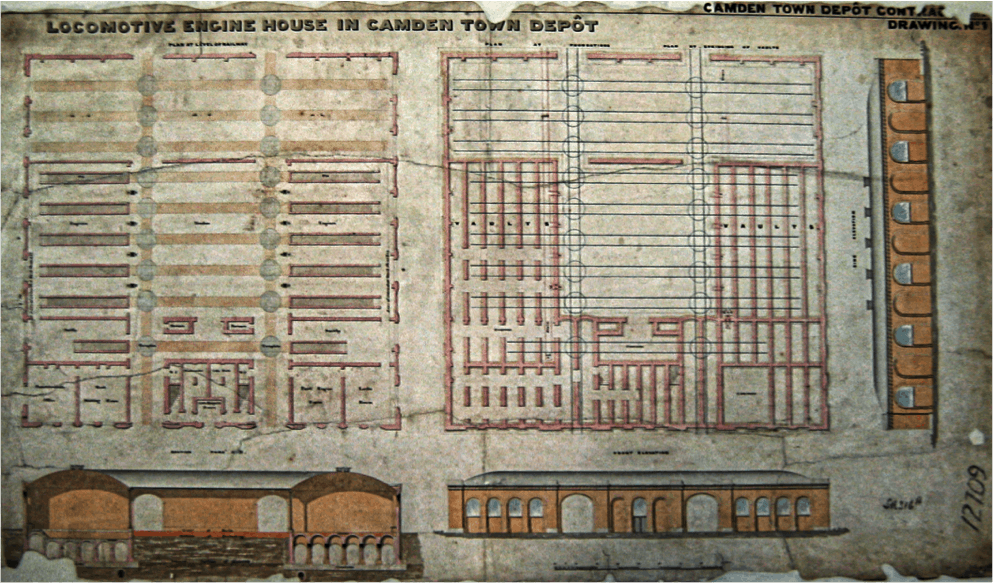

The main lounge was adapted as the drawing office and became a classical example of the organisation of engineering work, with an output averaging 30 drawings a week. Very little of this drawing output has survived, but a typical drawing featuring the Locomotive Engine House, Drawing No. 1 of the Camden Town Depot contract which was awarded to W & L Cubitt, is shown below.

Stephenson’s organisation of the drawing office later extended to his site supervision.

Discuss the quality of resident engineering staff he recruited and their subsequent influence in railway engineering.

Stephenson and Brunel

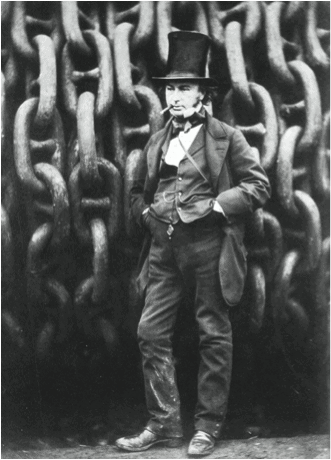

Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel were appointed as Engineer to two of the largest projects of their day before reaching their 30s: respectively the London & Birmingham Railway (L&BR), which opened in 1837 and the Great Western Railway (GWR), which opened a year later. They had each achieved a high level of professional respect, helped through their close working relationship with their famous fathers.

The intention of the two companies behind these projects was to share a London terminus, initially at Camden Station and later at Euston Station. The extension from Camden to Euston was therefore designed for two pairs of tracks and the western part of Euston reserved for the GWR.

However, as a result of Brunel insisting on a 7ft (2.1m) gauge, among other disagreements between the companies, the western tracks were never used by the GWR, which subsequently selected Paddington as its terminus.

Over the years that followed, the two engineers were rivals competing for commissions in the rapidly expanding railway network and for influence over its technical evolution, where Stephenson was clearly pre-eminent. Yet despite their public rivalry, they refused to make political capital from each other’s mistakes. They shared a strong professional respect for each other and, despite great differences in their character and upbringing, this warmed to support and friendship.

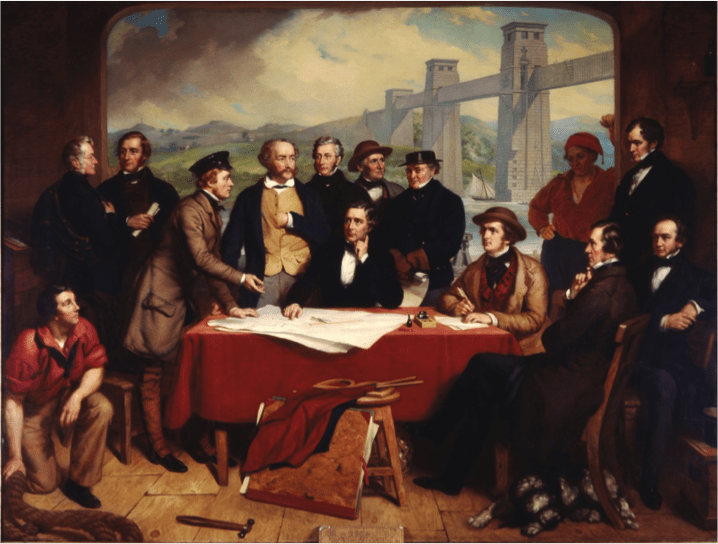

Among many examples of such support, here we see Brunel (right) and other eminent engineers in 1849 discussing Stephenson’s bold flotation of tubes for Britannia Bridge (ICE).

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was another endeavour that brought the two engineers together. Both were involved in organising the exhibition, and their projects were prominently displayed in the British Pavilion, enshrining their places in the pantheon of Victorian engineering. A GWR broad gauge steam engine dominated the heavy machinery area, while the main avenue featured a large model of Stephenson’s Britannia Bridge.

The launch of the Great Eastern in 1857 proved a most testing time not only for Brunel but also for his friend, whom he wanted at his side. Stephenson, although unwell, went to great lengths to provide support, writing to say:

I shall always be at hand happen what may to aid and do everything in my power without shirking any responsibility if need be.

They met for the last time on Christmas Day 1858 for dinner in Cairo, Stephenson having sailed to Egypt on his yacht Titania, while Brunel was recovering from the stresses of the Great Eastern, on holiday with his family. Each was attempting to restore his health after a lifetime of overwork, but a year later, within a month of each other, both were dead.